Undset was a timeless woman, in some sense. As an adult she lived in a home she had restored to medieval Norwegian style. Yet, she also wrote essays on feminism that could have been written in 1960. However, her conclusion to feminism was that a woman finds her ultimate worth or demise in her role as a mother. Her famous novel, Kristen Lavransdatter, has a heroin set in ancient Norway, with thought, desires and struggles that could be faced by any woman today. Unset has been paraded as a Norwegian feminist author and at the same time pushed aside as a Catholic author with an agenda. Sigrid Undset, at least to me, is as complex and intriguing as her most famous character.

Sigrid Undset became a Catholic in 1924 and four years later was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. Only nine women have ever received that award and Undset was the third and at 46 one of the youngest ever recipients.

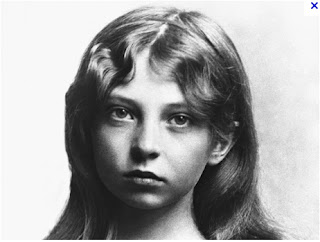

Sigrid Undset was born in May 20, 1882

in Kalundborg, Denmark and died June 10, 1949. At the age of two, her family moved to Norway.

Undset's father was a respected Norwegian archeologist and her mother was his illustrator and secretary. Both were atheists and raised their 3 daughters to think likewise. They were 'free-thinkers', went against the mold and sent their daughters to a controversial progressive, co-educational school. Their mother had them wear pants under their dresses. Undset's parents attempted to resist the strict and sometimes repressive nature of Norwegian Protestantism.

From a young age, Undset's father entranced her with the tales of ancient Norse sagas. So much so that as a child, Sigrid was motivated to learn to read in Old Norse and Old Icelandic. This passion was to carry through later in her novels. Her later writings included not just novels, but essays about Medieval Norway and translations of various Norse sagas and myths. It was not unknown for University lecturers

in Medieval European Studies classes to advise their students that the best way

to gain an insight into the medieval period is to read Undset's sagas.

After the death of her father when she was just 11, Undset went to several schools. Her family was poor and did not have the resources to send Undset to art school, as was her wish. So, at the age of 15, she attended a one-year secretarial school and took a job soon after as a secretary at the German Electric Company. She thought the work dull, but supported her mother and two sisters for 10 years, and wrote her first two novels during that time.

Her first manuscript, finished when she was 22, was rejected. “Don't try your hand at any more historical novels,”

wrote editor Peter Hansen. “It's not your line.” He told her to stick to contemporary topics. In order to get recognition as an author, at the age of 25 she published Mrs. Marta Oulie, set

in modern-day Norway. The opening sentence, “I have been unfaithful to my husband,”

guaranteed that the novel would be talked about in literary circles.

Eventually, she was able to make enough money from her writing to quit her secretarial job. Receiving a literary scholarship, she traveled Europe to write, ending up in Rome. There, she met Anders Castus Svarstad, a Norwegian painter, whom she married three years later. He had been married previously and had 3 children by his first wife. He and Undset had three more, one of whom was severely handicapped. The marriage was not a happy one and after Sigrid moved to Lillihammer with her children to prepare a new home in 1919, they were divorced.

The onset of World War I and the turmoil of her marriage caused Undset to look once again at her opinion of religion. Being raised an atheist, she was taught by her father to be a 'free-thinker' and to question the world around her. Evidently this pursuit of truth lead her to the ultimate truth of the Catholic Church. Seeing the immorality and ethical decline of her culture caused her to question the foundation of her beliefs. She first began her research of the ancient Norwegian Catholic Church from a purely academic standpoint, but this knowledge, combined with her love of medieval Norway, began the turn the tide against atheism. Where as before she had believed that man had created God, she now knew that God had created man.

Concerning her journey to the Catholic faith, she notes that “the war (World War 1) and the years afterwards confirmed the doubts I always had about the ideas I was brought up on — (I felt) that liberalism, feminism, nationalism, socialism, pacifism, would not work, because they refused to consider human nature as it really is.”

In 1920, she began writing Kristen Lavransdatter. In 1924, she entered the Church on All Saints Day. In 1927 she published the last book of Kristen Lavransdatter. In perfecting her passion, by seeking out success as an author, and by following her father's knowledge and love for her culture, Undset found the Church.

The following is from Elizabeth Scalia's essay published at FirstThings.com, titled "Sigrid Undset’s Essays for our Time" written on May 29 2012 (are we timely, or what?!):

|

| With her children, Anders and Maren Charlotte |

The onset of World War I and the turmoil of her marriage caused Undset to look once again at her opinion of religion. Being raised an atheist, she was taught by her father to be a 'free-thinker' and to question the world around her. Evidently this pursuit of truth lead her to the ultimate truth of the Catholic Church. Seeing the immorality and ethical decline of her culture caused her to question the foundation of her beliefs. She first began her research of the ancient Norwegian Catholic Church from a purely academic standpoint, but this knowledge, combined with her love of medieval Norway, began the turn the tide against atheism. Where as before she had believed that man had created God, she now knew that God had created man.

Concerning her journey to the Catholic faith, she notes that “the war (World War 1) and the years afterwards confirmed the doubts I always had about the ideas I was brought up on — (I felt) that liberalism, feminism, nationalism, socialism, pacifism, would not work, because they refused to consider human nature as it really is.”

In 1920, she began writing Kristen Lavransdatter. In 1924, she entered the Church on All Saints Day. In 1927 she published the last book of Kristen Lavransdatter. In perfecting her passion, by seeking out success as an author, and by following her father's knowledge and love for her culture, Undset found the Church.

|

| At her desk at home, writing Kristen Lavransdatter |

In the 1920's, Catholics in Norway were practically non-existent. Her conversion was very controversial. She was preached about from Lutheran pulpits and ridiculed by her contemporaries. However, this only spurred her on to write more.

Sigrid Undset was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1928. She was given prize money worth $42,000. In today's estimate, that would be worth ten times the amount. She donated the entirety of the prize to a charity assisting families with disabled children.

Sigrid Undset’s life was a heavy one, and it seems if she could not have joy, she was determined to have light; unwilling to live her life in ideological self-containment, it is not surprising that Undset would eventually come to call the Catholic church “home,” or that she would credit the saints with delivering her to its doors. Undset’s fiction is populated with vividly drawn characters—people of action whose narratives are built very precisely upon “human nature as it really is,” including the propensity for doubt and regret. To discover genuine men and women living boldly—not excused from those same propensities yet mysteriously delivered of them in the promise of a life in and with Christ, must have been for Undset a moment of staggering, irresistible illumination.

(from Undset's biography)

"But if you desire to know the truth about anything, you always run the risk of finding it. And in a way we do not want to find the Truth—we prefer to seek and keep our illusions. But I had ventured too near the abode of truth in my researches about ‘God’s friends,’ as the Saints are called in the Old Norse texts of Catholic times. So I had to submit.

But if you desire to know the truth about anything, you always run the risk of finding it. And in a way we do not want to find the Truth—we prefer to seek and keep our illusions. But I had ventured too near the abode of truth in my researches about ‘God’s friends,’ as the Saints are called in the Old Norse texts of Catholic times. So I had to submit.

By degrees my knowledge of history convinced me that the only thoroughly sane people, of our civilization at least, seemed to be those queer men and women the Catholic Church calls Saints. They seemed to know the true explanation of man’s undying hunger for happiness—his tragically insufficient love of peace, justice, and goodwill to his fellow men, his everlasting fall from grace. Now it occurred to me that there might possibly be some truth in the original Christianity."

When Joseph Stalin's invasion of Finland touched off the Winter War, Sigrid Undset supported the Finnish war effort by donating her Nobel Prize Medal on 25 January 1940. Her disabled daughter died in 1940, and her oldest son was killed in action shortly after. She fled to the United States because of her opposition to Nazism and the German occupation of her country. There, she untiringly pleaded her occupied country's cause and that of Europe's Jews, in writings, speeches and interviews. She returned to her home in 1945. During the war, the Germans had used her beautiful home as a brothel. She tried to write, but struggled. Sigrid Undset died four years later, on June 10, 1949. Her home is now a national monument.

|

| Undset on Norwegian 2 Kroner stamp, painting by her husband in 1911. |

|

| The 500 kroner note is of Sigrid Undset |

Very interesting post Lauren about Sigrid Undset!!! I enjoyed reading and WOW! “Don't try your hand at any more historical novels,” wrote editor Peter Hansen. “It's not your line.” Was he ever proved wrong! I finished the first book, The Wreath, and I told myself that I would take a break from reading to catch up on housework and spend time with the kids and their novels today. Well, I couldn't help but wake up early to start the second book, The Wife. I simply can't put it down. I LOVE this book SO incredibly much and am amazed by her writings! Now, if only I could talk my husband's company into moving to Norway! The Netherlands won't be too far away, so I do plan to visit! Would anyone like to join me? : )

ReplyDeleteI am so very jealous of your move. What a great adventure! Man, if you want to plan a trip to Norway while you're over there, I'll play the lottery every day, win, and join you! After I read Kristen the first time, I got myself on a Medieval Norway kick. Sigrid's got me hooked! :)

ReplyDeleteShe's still danish property.

ReplyDelete